The street names in Hong Kong are mostly dedicated to individuals, often members of the British royal family or the city's governors. Many of these names have ties to Queen Victoria. For example, places like Victoria Park, Victoria Harbour, and Victoria Prison carry her name. Naming places after authorities was a common practice to emphasize their prestige.

Queen Victoria ascended to the throne in 1837 when she was only 18, and she ruled for 63 years. Her reign is the second-longest in British history. Hong Kong, which opened as a port in 1841, was entirely managed by the colonial government by 1898 (excluding Kowloon Walled City). The city's development ran parallel to Britain's Victorian era, which is why there are so many places in Hong Kong associated with Queen Victoria.

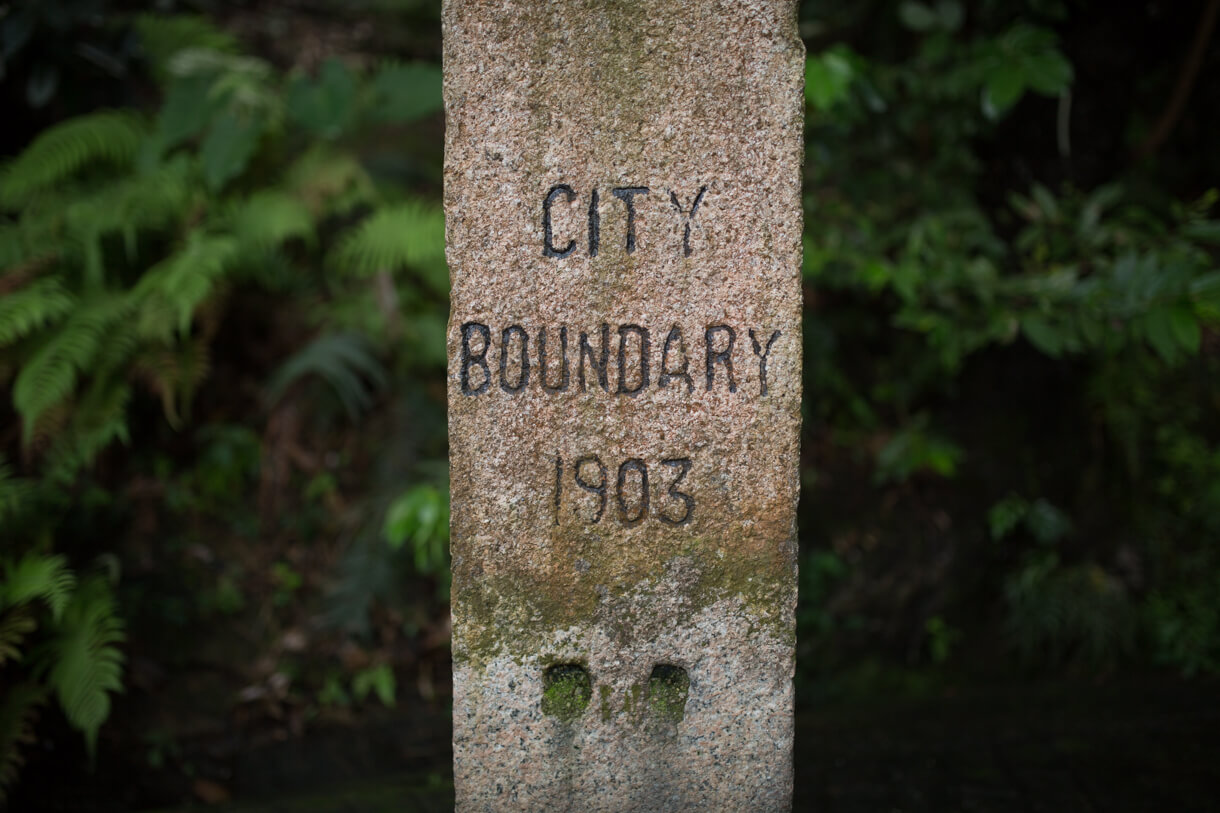

After the British landed in Hong Kong and started developing the coastal areas, they named the area "Victoria City" in Queen Victoria's honor. In 1903, the government defined the boundaries of Victoria City and marked them with six boundary stones, dividing the city into six major areas.

While the authorities used stones to mark the districts, the local Chinese community had their own way of identifying them, referring to them as the "Four Rings and Nine Districts". The Four Rings include the current areas of Wan Chai, Central, Sheung Wan, and West Point. These "rings" were further divided into nine districts such as Kennedy Town, Sai Ying Pun, Causeway Bay, and others.

.png)

Central became the center of British rule in Hong Kong. The building now known as the Government House was once the Governor's residence. It is located on the slope of Upper Albert Road, providing a panoramic view of the Central area. A building on Queen's Road Central, which once belonged to the French Mission, was initially the Governor's residence and later became the main office of the Hong Kong Government. This building housed key departments like the Legal and Health departments. Nearby is St. John's Cathedral, the oldest Anglican church in the city, a place of solace for Christians. The current Tea Ware Museum was originally the "Commander's Headquarters Building," which served as both an office and residence for the British Army Commander in Hong Kong, functioning as a military base.

The British focused their development on Central, while the Chinese primarily operated in Sheung Wan. There were certain complaints about Chinese lifestyle habits, such as the smell from burning incense, noise from musical instruments during religious ceremonies, or from the sound of firecrackers. This led to a policy where living spaces were segregated, although interaction still occurred, with Chinese often providing services to foreigners.

Back then, Chinese people came to Hong Kong from all over for business, viewing it as a temporary residence before returning home. Many were from the lower classes, working as laborers, craftsmen, or prostitutes, but there were also merchants who established businesses for intermediary trade. The British government largely adopted a hands-off approach, allowing the Chinese to organize their own management structures like the Man Mo Temple. This temple, a Taoist worship site, also played a role in resolving disputes and addressing various public affairs. Businesses contributed and united themselves through the establishment of Nam Pak Hong to tackle business-related challenges.

The history of Victoria City can still be seen in today's urban planning in Hong Kong. The stark contrast between Central and Sheung Wan provides a glimpse into the attitude of the British colonial regime towards the colonized. This contrast reflected among districts persists to this day.